It had been over a year since I last set foot in Madagascar, and much had changed. My previous visit had ended abruptly, with a hasty departure to avoid a tense situation involving a local authority and attempted extortion (see previous blog). This was quickly followed by the loss of our original mining site. Yet, amidst the challenges, we found a glimmer of hope with the discovery of a new site; a shallow gravel deposit in a nearby village that showed real promise.

August 2023 things got off to an encouraging start. Stones were unearthed at a brisk pace, and before long, they were sent to two local workshops to be cut and polished. From there, they were prepared for shipment to the UK.

However, the excitement of our early successes was soon dampened by the realities of navigating Madagascar’s complex export processes. Months passed as the team worked through layers of bureaucracy, gaining a first-hand understanding of why gemstone smuggling is so prevalent.

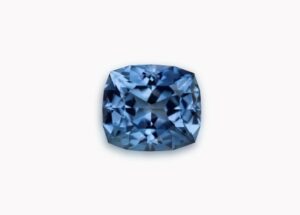

When the first shipment of gems finally arrived in London, it felt like a significant milestone. The stones were an array of colours, showcasing the incredible diversity that Madagascar is capable of producing, even from just one location. Most were around half a carat, but among them were some standout pieces, including a 3.68ct exceptionally clean blue sapphire cushion. Seeing the treasures our hard work had made possible was a thrill, but it was dampened by the disappointment of misidentified gems and subpar cutting. It was early 2024, and everything seemed to be falling into place. But as I inspected the stones, it became clear that this milestone was just the beginning of a steep learning curve.

While the team in Madagascar had checked them to meet shipping requirements, it was obvious they needed further gemmological training. All the stones I received had been classified as either sapphires or garnets, and indeed, we had been finding a fair number of strikingly beautiful red garnets. Yet, mixed in with these were spinel, chrysoberyl, zircon, quartz, topaz, and even some small andalusite. The colourless sapphires posed the greatest challenge, with many turning out to be either quartz or topaz.

To address the issue, we arranged for key members of the team to attend a rudimentary gemmology and lapidary course. This practical training would equip them with the foundational skills needed to improve their accuracy and confidence in identifying and handling the stones.

Garnet

Sapphire 3.66ct

Sapphire 2.49ct

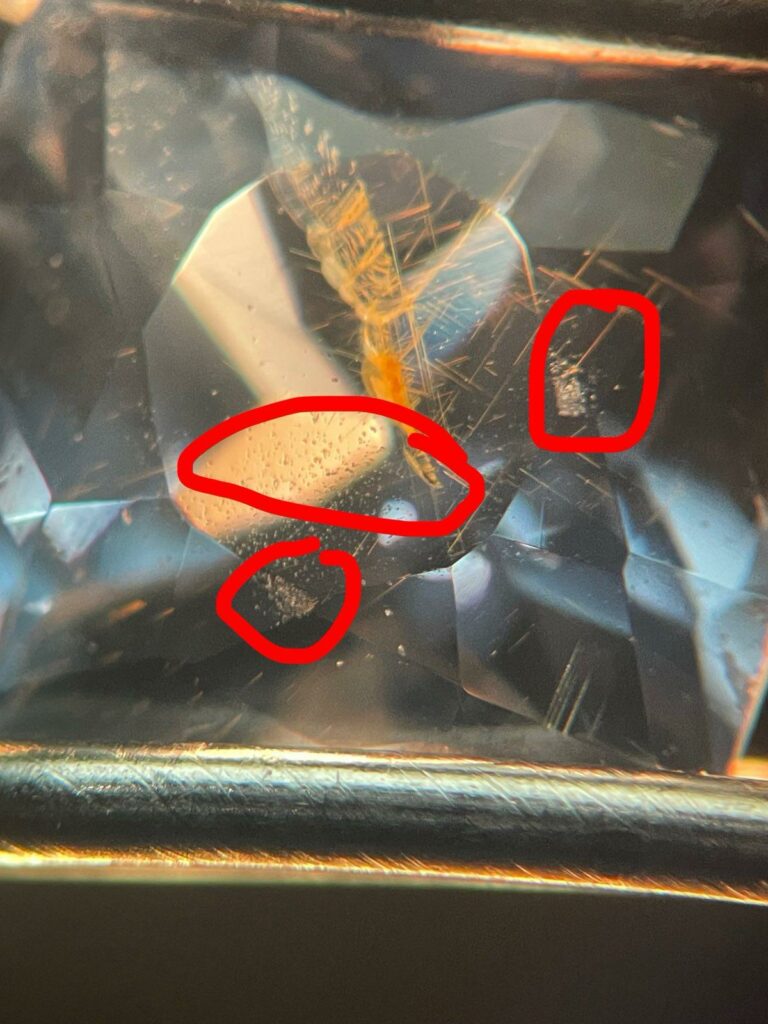

While misidentification was an issue, the quality of the cutting proved to be an even greater challenge. Many of the stones I received were unsaleable in their current state and recutting them in the UK was not an economically viable option. Each stone represented more than its potential value; it symbolized our commitment to Madagascar’s artisans. Ensuring the cutting stayed local has always been central to the project’s ethos. Fortunately, we had been meticulous in tracking which workshop had cut which stones. A quick analysis revealed a stark difference in performance; over 50% of the stones from one workshop were poorly cut, while the rejection rate from the other was less than 10%.

We made the difficult decision to stop using the lower-performing workshop and our efforts shifted to improving the output of the better-performing workshop. I felt guilty about taking this opportunity away, but maintaining high standards was essential to the project’s success.

We made the difficult decision to stop using the lower-performing workshop and our efforts shifted to improving the output of the better-performing workshop. I felt guilty about taking this opportunity away, but maintaining high standards was essential to the project’s success.

I sent the poorly cut stones to this workshop, accompanied by detailed descriptions of the issues. Thankfully, the head lapidary was highly receptive to feedback and recut the stones to an excellent standard. It became apparent at this point that ongoing quality control measures would be of great importance.

The greatest challenge we faced, however, came from within. We had established a three-team structure: the mining team, the administration team in Madagascar (consisting of two brothers), and the London team. The mining team was led by an older family connection to the administration team, someone with extensive experience in sapphire mining in the area from his younger days. His connections and expertise had been instrumental in achieving our initial rapid progress. However, he proved to be far more challenging to work with than we had anticipated.

While his enthusiasm for expansion drove swift development, it came at a significant cost. His accounting and recordkeeping were virtually non-existent, making it difficult for the administration team to manage the budget or maintain oversight of operations. He seemed more focused on rapid growth than on financial sustainability, often ignoring the limits of our resources. At one point, over eight hundred people were involved in the mining operation, causing costs to spiral out of control and straining relationships within the team.

Meanwhile, sales in the UK were sluggish due to a weakened industry, further compounding the financial strain. It became clear that we needed to pause operations to take a step back, reassess, and find a sustainable path forward.

After many discussions and phone meetings, we decided that our mining manager’s son would take over the operation. He had been working alongside his father and gaining valuable experience, showing great promise in leadership and a clear commitment to the project’s success. Importantly, he also demonstrated a stronger understanding of the developmental goals and overall vision.

To support this transition, we assembled a scaled-back team with a strict budget and well-defined operational parameters, sending them back to the mine with a renewed sense of focus. The father, however, expressed a desire to continue mining independently. To accommodate this, we agreed that he would establish his own separate, self-funded mine in parallel with our operation. The plan was to collaborate as allies, sharing resources and knowledge where appropriate. To recognize his contributions and help him get started, we provided a generous separation package.

At the time, this seemed like an ideal solution; a way to preserve the relationship while allowing both operations to thrive independently. Unfortunately, things did not unfold as we had hoped.

Upon returning to the mine in mid-2024, it became evident that the father now viewed us as direct competition. His behaviour grew increasingly erratic, driven by paranoia and a wounded ego. We later learned that, in his youth, he had worked with his brother in sapphire mining, only to be betrayed; a painful history that seemed to shape his belief that his own son had now turned against him. As rumours of this supposed betrayal spread through the village, the atmosphere became much less welcoming, making it a challenging place to operate. The shifting sands of perception are just as important as shifting the gravel, and even from afar I could sense us losing our footing.

Compounding the difficulties, he took control of equipment we had been using and planned to share, including the truck and the mobile office/camper. This significantly hampered our ability to continue mining. Despite these obstacles, our new mining manager maintained his composure, showing remarkable resilience. With his team, he focused on completing some of the development projects in the village that his father, unbeknownst to us, had abandoned. These included constructing a village well and laying a concrete floor in the village leader’s house, a notable improvement from the ubiquitous dirt floors.

It took considerable time to acquire a new truck and transport it to the mine. During this interim, mining activity came to a standstill, and the team temporarily left the site. Once the new truck was in place, operations resumed, though they were plagued by difficulties and production was minimal. Meanwhile, the father continued his own mining efforts, but his funds were dwindling, and he began making promises to the village that he was unable to fulfil.

Slowly, fairness and consistency began to win back the village’s trust. While we pressed forward with promised projects, the father’s erratic behaviour undermined his credibility, tipping the balance in our favour. This restored goodwill was very welcome, although the political landscape remained strained.

Up to the time I arrived in the village, mining had continued steadily. Production remained very limited, but the team had been developing their skills and the operation well. The father, however, had exhausted his funds and much of his influence. Despite this, he continued to stay in the village, surviving by renting out the original truck as a form of transportation. Only a handful of his most loyal team members remained with him, including one who, tragically, had recently learned his wife had left him.

It became increasingly clear that the father’s presence served little purpose beyond making life difficult for his son. For our new mining manager, the situation was both emotionally taxing and a constant source of frustration. Nevertheless, he persevered, showing an inspiring level of resilience and commitment.

Sitting in the office in London, I felt the weight of distance, frustrated at being unable to tackle these challenges directly. Eager to get back to Madagascar and reconnect with the team, I wanted to see the progress they had made and the lessons they had learned. Despite the setbacks, I was proud of what the team had achieved. For better or worse, this next chapter would shape the future; not just for the mine, but for the vision we had built together.

Alistair McCallum FGA

+44(0)20 7405 2169

Marcus McCallum Ltd

Second Floor

62 Hatton Garden

London EC1N 8LR

info@marcusmccallum.com